WRITER Colin Goodwin

We are in the Osteria delle Vigne, a typical Italian family restaurant just a few miles outside the town of Varano de Melegari. I sense that a culinary experience of epic quality is heading our way. We will be guided and served by Nicola Tambini, the grandson of the restaurant’s owner. There is no menu, no choice of wine; we will eat and drink what is put in front of us. I’m very happy to be left in the hands of Tambini and those of my lunching companion Giampaolo Dallara, founding father of the eponymous racing car manufacturer that he founded in Varano de Melegari in 1972.

Tomorrow is Dallara’s 81st birthday. At a special ceremony he will be given the first production Dallara Stradale, the company’s first road car. A simple machine, Lotus-like in concept, designed to be fun to drive on the road and on the track. Its chassis is carbon fibre, a material that this most fecund of racing car manufacturers knows very well. But first let’s go back a few centuries.

“My family has lived in Varano de Melegari and the surrounding area for 500 years,” explains Dallara. “At the beginning of the 20th century some Dallaras emigrated to the United States to work in the coal mines in Pennyslvania. I still have lots of relatives in the area.” It is fortunate for Varano de Melegari that Giampaolo’s grandparents weren’t part of that exodus, for today his company provides employment for hundreds of locals and presumably many more in the local supply chain in what has recently been branded ‘Motor Valley’. A valley that contains such illustrious names as Ferrari and Lamborghini. We’ll be visiting these companies shortly.

A plate of ravioli has arrived, four different types including artichoke parcels. A red wine from Parma is poured into generous glasses.

Born in 1936, Dallara grew up during the war. “There weren’t really any food shortages. I was very young, but I do remember fruit arriving in barrows from towards the coast and this being swapped for 30kg of wheat grown by our local farmers. The biggest impact the war had on our village was when 17 partisans were captured by the Germans and executed. As you can imagine, in a small community it removed part of a generation.

“Post-war conditions in Italy were tough and, to take our minds off the hardship, my father would take the family to watch motor races. Any races.” Was his father passionate about motor racing? “Yes, but everyone was. Absolutely everyone. I remember being taken to watch the Mille Miglia and being so incredibly close to the cars. An amazing spectacle.

“And then there were the drivers who, naturally, were hero-worshipped. The working people loved [Tazio] Nuvolari because he was closer to them in background. Achille Varzi had more style and tended to be followed by wealthier people.” These were experiences that triggered a life-long passion for racing and for cars. One that a young Dallara was determined to turn into a career. “I spent two years at university in Parma and then moved to the polytechnic in Milan. I wanted to take mechanical engineering but was unable to get a place. The only option was to study aeronautical engineering instead.”

An option that turned out to be a blessing. “A representative from Ferrari had been sent to the polytechnic,” says Dallara, “to find someone to work on aerodynamics. I put my hand up and was chosen. This was 1959 and in those days aerodynamics didn’t mean downforce, it meant improving penetration or, in other words, reducing drag.

“Ferrari was an incredible place back then. The atmosphere was amazing. I lived in a small apartment literally opposite the factory entrance. The people who you used to see coming in and out were quite something. I remember seeing Roberto Rossellini arriving with Ingrid Bergman to collect their new car, also the King of Sweden and the Shah of Iran. Royalty was always coming and going. Drivers, too. I particularly remember Phil Hill and Richie Ginther. Enzo Ferrari was like a god. I was scared of him and I think almost everybody else was, too.”

THE YOUNG DALLARA, STILL ONLY 23, WORKED UNDER CARLO Chiti, who was boss of the racing department. “Ferrari was competing everywhere, all the time. It was the time of the rear-engined revolution that Ferrari said was putting the cow behind the cart. The British were well ahead of the game.” It was a dream job, designing the most famous racing cars in the world in a heyday of motor racing. A dream, but not a perfect one.

“I was very junior, right at the bottom. I feared that my whole life would be spent in the drawing office. I would go to Monaco and other races, but I had to make my own way there and buy my own tickets. I was too lowly to be able to go with the Scuderia.”

Which is why, when Maserati approached Giampaolo with the offer of a job, he accepted. “The promise of going to races was the appeal of joining Maserati.” Clearly the young engineer was rather more than chief pencil sharpener in the Ferrari drawing office, because Mr Ferrari himself went to see Dallara’s father to ask him to persuade his son to stay at Maranello instead of debunking cross-country to Modena and

Maserati. All attempts to change his mind failed and for a time Dallara seemed to have made the right decision. “Soon after I started I was sent to Sebring, where we had two Tipo 63 sports cars racing. One was driven by Roger Penske and Bruce McLaren. I can’t remember the other car’s drivers. It was incredible. A fantastic experience for me.”

In between trips to the races Dallara worked on fuel injection, made by Lucas, for Maserati’s road cars. Not surprisingly Maserati, certainly not for the first or last time, was terribly short of cash. “They did a deal to sell some machinery to South America but never got paid,” says Dallara, “so the future looked bleak.” Certainly it didn’t look like a future spent watching Maseratis winning on the world’s racetracks. Once again Dallara was approached by a car company – a start-up as we’d call it today. “Ferruccio Lamborghini came to me with the promise that once the company was fully established we’d go racing.” Four years covered Dallara being plucked from college in Milan, working at the holy of holies in Maranello, joining Maserati and now moving to fledgling Lamborghini.

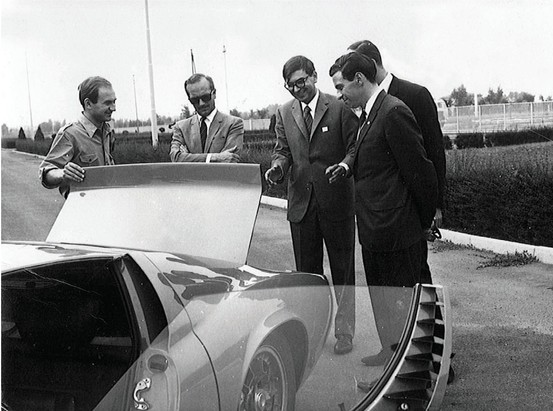

“We were so busy we never had time to go racing,” says Dallara. The small team at Lamborghini worked on the 350GT and then, two years after Dallara started at the company, it showed at the 1965 Turin motor show a bare chassis complete with powertrain that would underpin the fabulous Miura. The following March, at the Geneva show, the world saw the complete car wearing Marcello Gandini’s dramatic body.

“Fortunately we were so inexperienced that we didn’t realise the enormity of the task we were taking on. There weren’t many of us anyway and most of us were in our 20s. It seemed at the time that both Lamborghini and Bertone were going through a golden period in which everything they touched was perfect. Although we developed the Miura in only seven months there were hardly any serious problems to overcome.”